In December 1883 Vincent van Gogh went to live with his parents in the Dutch town of Nuenen, where his father was the pastor at the Dutch Reformed church. Having spent three and a half years struggling to forge a viable career for himself as an artist, Vincent arrived home hungry, impoverished and emotionally spent. His immense efforts had so far yielded nothing of substance, and the retreat to Nuenen was intended to give him time to repair his health, improve his finances and calmly pursue his art. When he left Nuenen two years later, in November 1885, he had amassed a large body of work, including The Potato Eaters, his first accomplished and original large-scale canvas, but his time there had been fraught with incident. The New Potato Eaters looks back at Van Gogh’s Nuenen period, tracing his artistic development and setting his work in a broad historical context. Two pieces in verse and a set of new portraits of present-day Nuenen residents reflect creatively on Van Gogh’s achievement. Innovative, original and beautifully designed, The New Potato Eaters takes a fresh and distinctive look at Van Gogh in Nuenen.

The New Potato Eaters: Van Gogh in Nuenen 1883–1885

Edited by Paul Williamson

Contents

1 Introduction: Before Nuenen

Paul Williamson

2 Van Gogh in Nuenen, 1883–1885

Ton de Brouwer

3 Vincent and the Gospel of Work

Paul Williamson

4 Head of a Peasant Woman

Colin Wiggins

5 Towards The Potato Eaters: The Long-Awaited Genesis of a Masterpiece

Laura Prins

6 Van Gogh’s Colour

Stephen Hackney

7 Fields: Vincent to his Brother

Simone Kotva

8 Self-Portrait with the Pastor’s Boy

Martin Huxter

9 In Many Places

Catherine Pickstock

10 Van Gogh and the Camden Group: Reflections and New Directions

Stephen Hackney

11 The Trouble with Rembrandt: British and Dutch Portraiture in the Eighteenth Century

Robin Simon

12 Bacon and Potatoes: A Marvellous Vision of the Reality of Things

Amal Asfour

Afterword

Hugo Ticciati

To read Paul Williamson’s introduction to The New Potato Eaters click here.

The New Potato Eaters

Edited by Paul Williamson.

Published by Festival O/Modernt, Cambridge & Stockholm 2015.|

General editor for O/Modernt publishing: Paul Williamson.

Paperback with wrap, 272 x 240 mm, 136 pages, 100 illustrations.

Designed by Teresa Monachino.

Paper by Fedrigoni.

ISBN 978-0-9928912-1-3

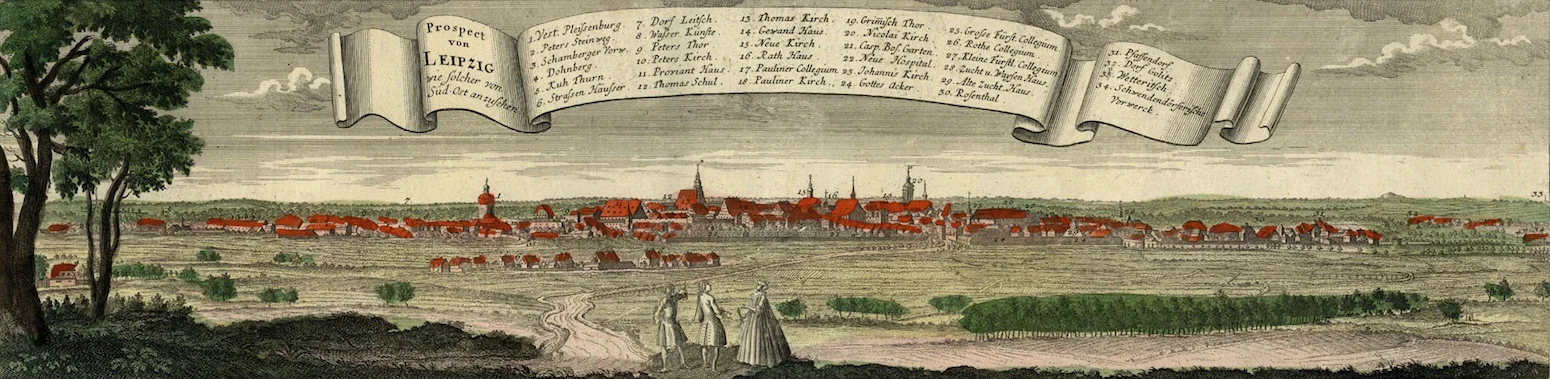

Vincent van Gogh, The New Potato Eaters, 1885.

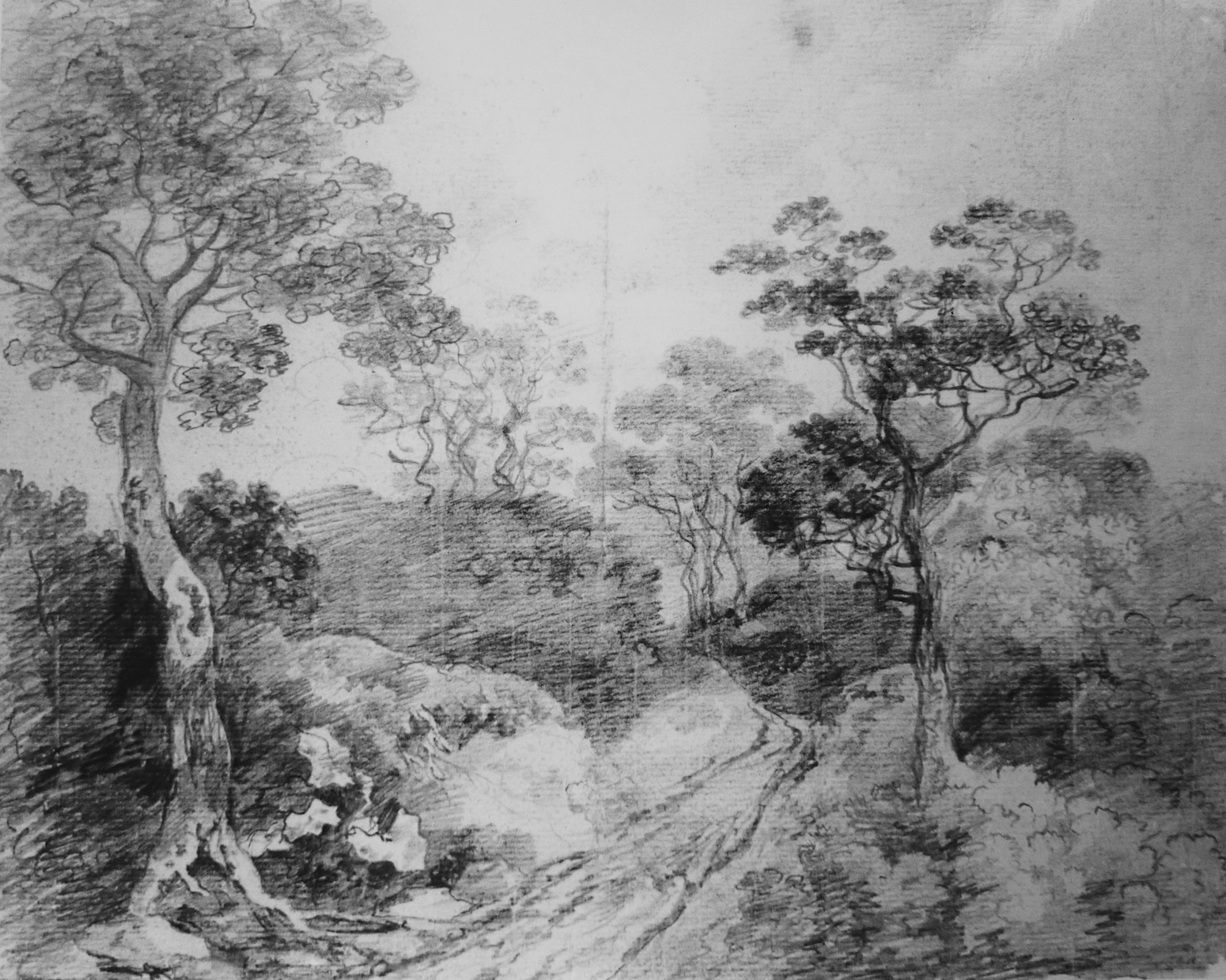

Vincent van Gogh, Head of a Woman. 1884–5.

Detail from the wraparound dust jacket of The New Potato Eaters.